|

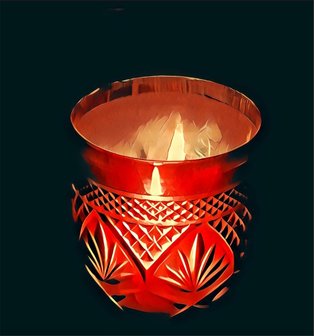

Then the Lord said to Elijah, “Go, stand in front of me on the mountain. I, the Lord, will pass by you.” Then a very strong wind blew. The wind caused the mountains to break apart. It broke large rocks...But that wind was not the Lord. After that wind, there was an earthquake. But that earthquake was not the Lord. After the earthquake, there was a fire. But that fire was not the Lord. After the fire, there was a quiet, gentle voice. (1 Kings 19:11, 12) The Fireplace and the Candle I like my fireplace-- Warmth with light and sound. (Three to one over my furnace!) Sometimes, Lord, you are my fireplace. The warmth drawing me near The light--now brightly fascinating, now glowing and comforting The sounds--my favorite part--unpredictable, surprising, cracks, pops and bangs So very alive and vital. Sound with a dash of fury: Laughter or sobbing A friendly greeting or a rebuke Wisely spoken words (apples of gold, according to Solomon) My wife's prayers over me and mine over her. The audible liturgy of my life. More often, though, you are my candle. Like the little votive in the deeply etched heavy red glass on my desk. (I light it for prayer time--or when I just want to sit and think, maybe jot down a few thoughts.) A little light, A little warmth, And silence. Its silent flaring and flickering become The back and forth of my prayer The up and down of my mood The to and fro of my relationships The ebb and flow of my life. I learn from the wax and the wick: united, they receive your flame and gladden the space around them with A little light, A little warmth, And silence. My fireplace is nice, and has its season, but mostly I prefer my candle. No rousing to stoke, prod, poke and feed it, to get it just right. Just me and a candle. I sit back and we meet In the light In the warmth But mostly in the silence. (c) 2017 Larry Pizzi

1 Comment

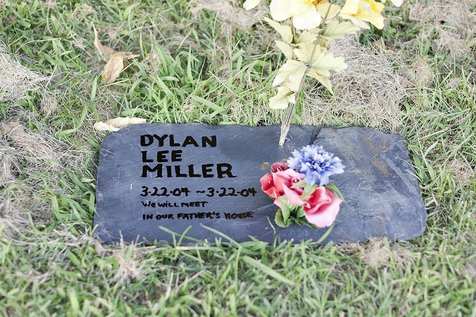

I’m writing the first draft of this week's offering on Dylan Lee Miller's birthday, March 22, 2017. He would have turned 13 this day. I never met Dylan. It's a pretty good bet that very few people ever met him. My part in his story began on January 3, 2009. Since 2003, I had often visited the Mariawald retreat house in Shillington, Pennsylvania. On those visits, I had gotten into the habit of seeking a quiet space outdoors by walking through a nearby cemetery, the subject of a previous blog post. Near the back edge of the cemetery, I tripped over a temporary marker in the winter-brown grass and gravel. It read Dylan Lee Miller, March 22, 2004-March 22, 2004. It was askew and mold had begun to encroach on the lettering. It struck me like a bullet. This child was buried five years ago, and there was no gravestone, no permanent marker. Clearly there would be none; the temporary marker was well on its way to the corruption that dooms all things material. There may be a record somewhere in the cemetery archives of the plot and its resident, but this boy's grave was going to disappear sooner rather than later. It was in the uppermost reach of the cemetery by the wooden fence that divides the graveyard from the forested ridge; it would surely go unnoticed. Nearby was another temporary marker just as old as Dylan’s, but it was decorated with Christmas flowers. No stone, but someone had remembered recently. For Dylan there was no evidence of remembrance. The decaying temporary marker seems to have been unnoticed and untouched. Just as they had in 2003, the words of John Donne’s Meditation XVII bubbled up: No man is an island, entire of itself...any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee. For Donne, every time he heard a funeral bell tolling a stranger’s death, he was reminded not only of his own mortality, but more importantly his oneness with the unknown dead, and, therefore, with all of humanity. Although Dylan was only alive perhaps a few hours, I felt diminished by Dylan’s death. I ached at the thought of his marker disappearing. When the bell tolled for Dylan, it tolled for me, and the peals of that tolling echoed in my spirit. Determined to at least stem the tide against the decaying marker, I found some artificial flowers that had blown from their graves and shoved them into the ground in front of the marker. I fixed the marker as best I could and then gathered several large rocks and used them to surround it. I wondered all that night: Why was there no marker after five years? Someone loved him enough to give Dylan a full name rather than bury him as simply “Infant,” which one can often see in cemeteries. What happened to Dylan’s parents? Are they themselves dead? Are they simply too poor to Mark the grave? Are they able but unwilling for some reason? So I pray for the forebears of Dylan Lee Miller. On my next trip, some months later, the marker was still there, but the stones had been removed. I wanted to do something, but what? The convent and retreat house where I was staying were once part of a very large and wealthy estate. In the woods there were the remains of an old hunting lodge. Only the foundation and the slate roof tiles survived. Here, I came upon a nearly rectangular piece of slate. It was much thicker than most pieces. One side was smooth. I thought I could fashion it into a grave marker for Dylan. After dinner, I put the slate in the car and drove to a drug store, where I bought a permanent marker and a ruler. I took the slate back to the room and scrubbed it in the tub. While it was drying I discovered writing on the back. Scratched into the stone were some words I could not decipher, except for “give them life abundantly.” Could this be a reference to Jesus’ words , “I am come that they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly” in John 10:10? Someone had already turned the stone into a marker of sorts, so I took that as a good sign. I wrote Dylan's name and dates on the front with the words “We will meet in our father's house.” I took it to the cemetery and laid it over the temporary marker. It had two holes in it because it had once been a shingle, and into these I shoved the artificial flowers as a way to somewhat fix it. I prayed that the groundskeeper would be merciful and would leave the marker alone. My last visit was in 2013, and the marker was still there. Every person’s death diminishes me, even if that person was stillborn or lived less than the span of a single day. Dylan's grave reminds me, as the tolling bell reminded Donne, that I cannot help but be involved in all of mankind. Rest, Dylan. Someone thought of you today. You're part of the history of mankind, a part of my history, a part of every person’s history. Donne was right. (c) 2017 Larry Pizzi

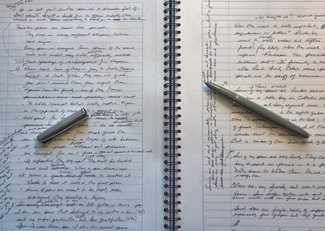

My father-in-law died this week. He was in his 99th year. I wrote the draft of this blog with his pen, a vintage Parker 51 made in 1946. As you can see from the photograph, I own lots of pens, all fountain pens and dip pens. Each one of them works. The criterion for adding a pen to my collection is that I must be able to write with it. Why would one need more than one or two fountain pens? The answer, for me, lies in the fact that fountain pens and people have much in common. Fountain pens are tipped with a nib, a sometimes beautiful and always fascinating bit of engineering that draws air into the pen to allow ink to flow from the pen. Fountain pens need to breathe air to function. Some nibs are gold; some are steel, some are alloys of precious metals. Some are broad-tipped; some are medium, and some are fine. Some are flexible and can lay down script in various widths with a flourish. Some are firm and some absolutely rigid. Each has its own use, its own way of producing words on a page. In other words, fountain pens have personalities. Fountain pens are indeed much like people. They come in many different shapes and colors and sizes. Each pen is unique. Fountain pens of the same make and model may even write slightly differently because of small differences in the nibs. For most who use them, a fountain pen is not just another pen in a drawer full of ballpoints and pencils bought in bulk from an office supply store, mixed in with pens advertising a bank or a car dealer. Fountain pens are meant to last. When they run out of ink you don't discard them, you refill them. Because the pen is meant to last, it needs care. The whole concept behind writing with a fountain pen is pretty much the opposite of writing with a pencil or ballpoint pen. You don't apply pressure to write with most fountain pens. To do so produces bad results and will probably damage the pen. You simply guide the pen as it glides over a layer of ink between it and the paper. Excess stress and pressure are harmful. You can't force a fountain pen and expect it to respond well. The right relationships among pen, ink, paper and hand are essential. It can be a challenge at first, but once you seek out and understand a particular pen, it is a joy to write with. If neglected, a fountain pen dries out and stops working. It must be treated well and maintained constantly. If a pen dries out, it takes some effort to restore it. Better to treat it well in the first place. Since fountain pens are meant to be kept, even treasured, they can develop a legacy. In addition to my late father-in-law’s pen, I also own pens that belonged to my mother-in-law, my wife's grandmother, and my wife’s grandfather. I also own pens that are very old but of unknown provenance. As I write with one of these I sometimes wonder: What has it “seen?” Who bought it? Was it given as a gift? Was it used to write important, life-changing signatures or correspondence? Was it used lovingly to write notes and letters to family and friends? Was it used begrudgingly to write a check to pay a bill? The possibilities are endless. It's fascinating to me to picture other hands holding the same pen that I hold in mine. Fountain pens, like people, are the stuff that memories are made of, both good and bad. Some fountain pens are old and distinguished; others are bold and brash. Some draw attention to themselves. Some simply do their jobs without a fuss. Some are easy to get along with; others need more care and patience. I have several humble school pens. I recall as a little boy in Catholic school being required once a week to surrender a quarter to the eighth grader at the school store (wobbly card table in the hall) to buy a box of fresh cartridges. I look at these pens and wonder about the students who used them, noting that the pens often have bite marks or chewed ends. Some of my pens are very hardy. They can withstand being dropped or jammed into a pocket or briefcase. Nothing seems to bother them. Any ink and any paper will satisfy them. Others are very finicky or fragile and won't work on anything but their own terms. Some prefer certain inks and rebel at others. Some write well on fine paper but create a mess on common copy paper. Back to the original question: Why own more than one fountain pen? One might ask, why have only one friend or only one kind of friend? Why mix with only certain people and miss out on the richness of different people? Yes, fountain pens and people have a lot in common. If I re-read this blog post and substitute people for fountain pens, it all makes sense. It is a challenge for me sometimes to care for people as well as I care for my pens. Like my fountain pens, all people are unique, have a story to tell, and are worth my time and effort to understand them, to find in them the peace of a mutual relationship and perhaps the joy of a friendship. (c) 2017 Larry Pizzi

With apologies to Karen Carpenter, rainy days and Mondays rarely get me down. Never? Well, OK, I’ve been trod under by more than a few Mondays in my 64 years of life. But rainy days--never. I like rainy days (and nights). I don’t think of them with the usual adjectives: dark, dank, dreary, gloomy, miserable. I’m very fond of pleasant sunny days too, but in a perverse sort of way, rainy days warm and comfort me, whether outdoors or in. Pretty ironic for someone who spent more than a few rainy days outdoors, forced on him by Army life. The obvious question: Why? I'm not sure, but it may have something to do with leaves and wet tennis shoes (Converse All Stars, to be exact). It was 1965. I was 12. It was late fall, probably November, which means my Army-officer-father had been deployed to Korea for at least five months. For some reason I was out in the rain on an aimless walk. I have no idea what spurred me to do such a thing in the days before Gore-Tex, but I did do it. The trees to my front were denuded; just a few straggling leaves defying the breeze and the rain. The expanse of rising fields to my left, the far eastern edge of the fairgrounds, was brown and matted. To my right were the soggy beginnings of a new housing development, mostly basements and foundations. Ugly but promising. I was not so much walking as trudging. My canvas tennis shoes were mostly hidden by the leaves through which I plodded . I was not in a hurry. I had no destination. It had not been raining so hard or so long as to soak the leaves that were my sidewalk. Each step overturned dry leaves and produced the familiar crackle and crunch. That’s all I remember. I do not remember leaving the house. I do not remember returning home.The reason for the walk escapes my memory. As vivid as it is visually, the scene is without meaning, except for one thing. Even though I have no memory of how I felt during that walk, every time this memory presents itself I feel happy and content--feelings that are not common for me, nor have they been for many years. What I see is simple; a grey and brown scene, fields, trees, dug up lots, but mostly my wet shoes turning over the leaves, the sound of the leaves mixing with the sound of the rain and the breeze. November in Pennsylvania. Despite the absence of feelings and motive, the memory is pleasant to me even now, more than a half-century later. I have very few vivid childhood memories, and when I try to recall my youth, this scene pops up first more often than not. It’s a very short scene, less than a minute, in a very long play, the end of which is nearer than its beginning. I have no idea why I feel content when I recall it. Being more than a little prone to melancholy (I’m Eeyore, not Winnie the Pooh.), I can only conclude my affinity for rain-sodden days is a gift, an inexplicable, unmerited grace from a blink in my mind’s eye of tennis shoes and leaves. Whatever else is bothering me, I can always look out the window and admire the beauty of the day, rain or shine. So I must add thankfulness to the pleasant feelings the memory brings. At this point in my life, I’m not really interested in peeling back the layers of the onion, to discover the cause-and-effect of this memory. I’ll just count it as a gift, a small cause with a big effect for which I’m grateful. Since I began by mangling a song, I’ll end with apologies to Fred Ebb and Frank Sinatra. If I can find contentedness in a 50-year-old memory, I’ll find it anywhere. I just have to look with my heart as well as my eyes. Who knows? Maybe I’ll see it best with my eyes closed and my heart open. (c) 2017 Larry Pizzi |

Larry Pizzi50 years of photographs and 35 years of keeping a commonplace book. Archives

March 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed