|

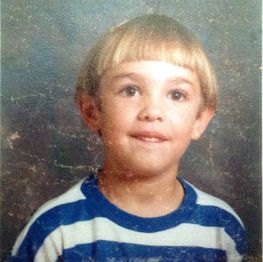

When I was a young Army second lieutenant in training for my first assignment, I had to go through a course called “Crater Analysis.” We examined fresh bomb and artillery craters to learn how to identify the source and type of the explosion that created them. What I remember most about the craters is that they were ugly and ominous: huge holes that scarred the earth. They were hot and still smoking. Shards of steel shrapnel, jagged, twisted and still dangerous, protruded from the sides and littered the ground. The earth around the crater was scorched black; all the vegetation in the vicinity was blasted. A jagged, ugly, and grim hole in the earth. Not many months later, I found myself stationed in Germany. Since I was a very junior officer, there were no American houses available, so my new wife and I lived in a little farm village of about 180 souls ten miles outside of Nuremberg as the crow flies. The rural countryside of Bavaria is beautiful, and when time allowed we would take long walks across farm fields, meadows, and through beautiful woods. One day, as we were walking, I noticed that, even though we were in a flat meadow, we were walking up and down. We would walk a few yards, dip downward ever so slightly and then walk upward. The effect was slight but noticeable. It suddenly occurred to me that the source of our up and down movement was old bomb craters. Despite the passage of three decades since the round the clock carpet-bombing of Nuremberg in 1945, and despite nature’s skill in healing herself, the craters were still there, their jagged edges softened and covered with new life of grass and trees. Many years later, having gone from second lieutenant to lieutenant colonel and nearing the end of my career, my 12-year old son died of brain cancer. The effect was obviously devastating and not unlike the effect of a bomb or artillery shell on its target. Today, 22 years since my son’s death, I take comfort in the images of the bomb craters. When my son died, the hole in my life, in my self, was like the fresh crater I had seen in training: scarred and grim. In the years since Tim’s death, the hole created by his absence has softened and smoothed over, like the craters in the fields and forests my wife and I frequented on our walks. But the hole is still there. And I would want it no other way. I do not want the hole to go away. I am, however, blessed by the grace of God and the friendship and fellowship of family, friends, and community who smooth and soften the hole over the years. Even today, time and grace are healing the once fearsome crater. When loss is fresh, we wander confusedly and fearfully through the wilderness of grief. But as the Old Testament prophet reminds us, God’s grace works to “fill the valleys and level the hills, [To] straighten out the curves and smooth off the rough spots.” (Isaiah 40: 4, 5) As we travel through our grief with a loving God, with friends and with family we do not forget our loss. With their help the crater’s scar becomes less jagged, less ugly, less fearsome, but no less real. That’s the reality of grace, family, friendship, and community. (c) 2018 Larry Pizzi

12 Comments

|

Larry Pizzi50 years of photographs and 35 years of keeping a commonplace book. Archives

March 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed