|

In 1963, I was 10 years old and in the fifth grade at St. Leo's Catholic School in Fairfax, Virginia. It was in the fall of that year that I decided that I had but one future: to be a priest. I had been an altar boy for a year. (Girls weren't allowed to serve then so we were not yet called altar servers.) I had been admitted to the service after passing a strenuous examination by Sister Bernadette. Satisfied that I knew the entire mass and Latin, she informed the priest that I was ready for duty. It's not clear to me today what brought about this absolute certainty of my vocation. I loved to serve mass and probably felt that my Latin mastery put me a notch or two above most of my male classmates. (My female classmates didn't count toward my stock of self-esteem at age 10.) I do remember, though, that for some reason I kept my ambition a secret. I vividly remember waiting for the opportunity to steal a needle and thread from my mother's sewing basket as well as some old bath towels from her neatly folded store of rags. (Yes, the irony struck me even then that I was setting off on the spiritual journey by brazenly breaking the seventh commandment.) I took my loot to my room and made a crude set of altar linens, a chasuble, and a stole, all of which displayed ample evidence of the fact that I did not know how to sew. I “embroidered” a cross on each piece. Using a paper cup, some grape juice, and a squished piece of white bread I proceeded to imitate the priest celebrating Mass. I took it all quite seriously. My assumption that I would be a priest lasted for five years. I had a like-minded friend in the 10th grade. We talked for hours about what seminary must be like and how great it would be to finally be a priest. Alas, during those five years two seismic events rocked my world: The Second Vatican Council and puberty. The former left my Latin skill superfluous and the latter...well no need to elucidate. By my junior year in high school, while still serving and attending Mass faithfully, the certainty of my vocation faded. Five more years passed, then marriage, an Army career of 21 years, and two children. Occasionally in the more than 50 years since I “decided” to become a priest, I have wondered: Did did I screw up? Worse yet, had I sinned? Was my life based on good but wrong choices? Had I turned a deaf ear to a genuine call? Such questions, now, more than half a century later, are more amusing than troubling. If I did sin by turning away from God's calling, he certainly has employed a strange manner of punishment and consequence: the love of a good and godly woman, children, family, and not one but three separate and successful careers. In all of this is the infinite mercy of God. Perhaps I did ignore a genuine call. Even if I did, God's love and grace towards me were not diminished one whit. This is true of big choices like a vocation and little choices each day--some choices are good and some are not and neither has any effect whatsoever on God. They may change me for good or for ill, but they do not change God. His love for me is not changed by my actions. It’s why the biblical writers were so fond of the refrain, “His love endures forever.” I suppose that’s why it’s called perfect love. As I've aged, the world I was so sure of in my earlier years, the world of black and white, has not only morphed into tones of grey but into vivid colors. When I was a little boy, Sunday nights meant gathering around the TV with my brothers and watching Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color. The one-hour TV show began with a song, the first words of which were “The world is a carousel of colors!” sung against the backdrop of the iconic Disney castle and bright multi-colored fireworks. At least I assume they were colorful. We had a black and white TV. Watching the Wonderful World of Color on a black and white TV is an apt metaphor for my earliest ability to reason and my earliest thoughts about the world around me. We eventually got a color TV when I was in high school, about the same time, to continue the metaphor, that my absolute conviction of my calling in life begin to fade. I've wrestled many times in the last half century with the world around me and my part in it. I have come to a point today where I can feel liberated by the fact that I'm not smart enough to know what I don't know. Being less certain about things is not troubling, it's freeing! God's grace, his mercy, and his forgiveness are prisms that radiate his light and love. They result in color. The world looks a lot better in color. (c) 2017 Larry Pizzi

2 Comments

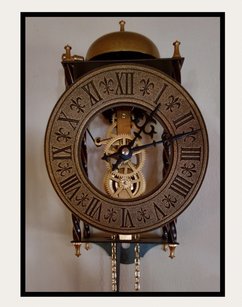

In a previous post, I wrote about my passion for collecting fountain and dip pens. I noted that these pens were very much like people and that they teach me much about myself and my relationships with others. The same is true for my other collection mania: clocks. I have more than 100 clocks. Some are fairly modern; some are vintage, and some are antiques. Some are weight driven; some are pendulum driven. Some are spring driven, and some are electric. Some are wall clocks and some are mantel clocks. Some are even vintage or antique alarm clocks. Like pens, clocks teach me much about myself and my relationships with others. Like people, some of my clocks need more attention and care than others. Some need winding once a week, others twice a week, and others daily. Some are temperamental and sometimes irritating. Some are laid back and easy going. Each clock (except those that are weight driven) gets wound with a different key. As in the real world, the world of clocks is not a one-size-fits-all world. Old clocks need more than just being wound to work properly. As a rule, a clock must be perfectly level to function. When I first started collecting clocks, I used a bubble level to keep the clocks straight. Some clocks, though, would balk at being perfectly level. I soon learned the secret to leveling a clock: toss the rules and the tools and listen to it. The ticking in clocks comes from the motion of a pendulum or a flywheel, back and forth. A working clock sounds like “tick” in one direction and “tock” in the other. In cases when levelling a clock with a level doesn’t work, I have to adjust it by listening to it. An out of sorts clock may sound like “tick-tick” or “tock-tick” or even “tock-tock.” Each clock is different. By listening, I learn what each clock needs to work properly. Just as with people, each clock is unique, and I must treat it accordingly. It all begins with listening. I have a couple of wall clocks that simply won’t work unless that are so far askew that they are actually crooked on the wall. So I must accept the quirkiness of a clearly crooked clock hanging on my wall, and smile when I see it. I could insist that the clock hang straight, but then the clock would not work. I would have an aesthetically pleasing, perfectly level clock that would not tell time. It’s as if the clock is saying, “Please accept me for who and what I am, quirks, idiosyncrasies and all.” Collecting clocks, like collecting anything antique, is a mixture of archaeology and anthropology. I dig through the internet to look for clues to the age or the maker of a clock. I scour the clock with a magnifying glass and a flashlight looking for dates, numbers, markings, words, anything that will help me place the clock in its historical context. But there's also some anthropology involved. A Victorian inspired design is very different from an art-deco design. Each tells me something about the aesthetics and values of the maker and of the person who first made or bought the clock. I have more than one clock that proves the old saying, “There's no accounting for taste.” One of my oldest clocks has a common saying in Old Dutch written on it: “To each, his own!” I wonder about previous owners and imagine the clock in their lives and homes. Perhaps this ornately carved gingerbread clock had pride of place on a mantel in a drawing room. Perhaps this lowly alarm clock wakened someone grudgingly to his daily tasks. (Old alarm clocks didn’t have snooze buttons!) Some of my clocks are “fakes.” I do have a couple of Art Deco clocks from the early 20th century, but some are more recent, made to imitate an older design. Not every clock is what it appears to be. But I care for it the same as the genuine one. Like a person, each clock has its own story, and I love to discover and listen to that story. Many of my clocks strike the hour and half-hour. Some chime as well as strike, making a melody to announce the time. Some used to strike, but don't anymore. Some still strike, but not always the right hour. These clocks are still beautiful to me, even if age or abuse has limited their abilities. More than once, I have bought a battered old clock because my wife has seen past its ugliness to the beauty that might be restored with some loving care. As with people, some clocks can have limited abilities, but still have great worth and a beauty of their own. Over time, I learn to identify a clock by its strike or its chime, even if I'm not in the same room. As with people, I don’t actually have to be with the clock to enjoy it and to receive from it. My clocks remind and teach me daily things about myself and my relationships with others. As different as each clock looks, sounds, and acts, I still take pleasure in caring for it, looking at it, and listening to it. Each has its place. Each enriches me. (c) 2017 Larry Pizzi

Of all of the companions traveling the yellow brick road to the Emerald City, Dorothy was certainly the most courageous. What, though, was her greatest act of courage? Slapping a lion? Confronting the Witch of the East? Acting heroically to save the Scarecrow? All of these are fine examples, but for me Dorothy's greatest act of courage was stepping out of her house and into Oz. Her home was familiar and, despite the wild ride, seemed safe. But it was also ordinary. So ordinary, so familiar, that it was monochrome or sepia, depending on which version of the film you watch. It was safe, but it was also dull, drab, and, but for Toto, lonely. She tentatively cracks open the door to see a land completely unfamiliar; so unfamiliar that it was in living color. This was clearly not Kansas. It was very different and, therefore, somewhat frightening. Yet she widens the crack and steps out to beauty, strangeness, and danger. That step from the safe and familiar is her first step forward. She had to leave the house to get home. There are times in my life when I feel like I have just landed in Oz. I need to take a step out of the familiar grey and into the unfamiliar color. But that step is frightening. I don't particularly like the monochrome world, but I'm not quite ready to step over its threshold into the beautiful but frightful unknown. I timidly and hesitantly peer through the crack. Dorothy Gale, meet Leonard Cohen. Cohen’s song “Anthem” is a poem that resonates with me, with my paralyzing fear of the unknown that keeps me from moving forward: Ring the bells that still can ring Forget your perfect offering There is a crack, a crack in everything That’s how the light gets in. On the day after Cohen’s death, Quartz.com writer Cassie Werber, wrote an extended commentary on the chorus to “Anthem.” She quoted a Cohen interview from 1992 in which the songwriter tells us-- The future is no excuse for an abdication of your own personal responsibilities towards yourself and your job and your love. “Ring the bells that still can ring”: they’re few and far between but you can find them…. This is not the place where you make things perfect, neither in your marriage, nor in your work, nor anything, nor your love of God, nor your love of family or country. The thing is imperfect. And worse, there is a crack in everything that you can put together: Physical objects, mental objects, constructions of any kind. But that’s where the light gets in, and that’s where the resurrection is and that’s where the return, that’s where the repentance is. It is with the confrontation, with the brokenness of things. Change is hard for me. I put it off under the guise of waiting for a better time. I especially don't like situations where I’m confronted with the possibility of failure. Waiting for the perfect time and fear of failure amount to the same thing and produce the same results: paralysis. Nothing in this world is perfect. Change requires the faith and courage to widen the crack, to let the light in, and to step over the threshold. I don’t want to, but unless I do life will remain colorless, and I'll never get home. (c) 2017 Larry Pizzi

|

Larry Pizzi50 years of photographs and 35 years of keeping a commonplace book. Archives

March 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed